SAFE Resource Hub

Demystifying and deconstructing abortion, one question at a time

Resources

Perspectives

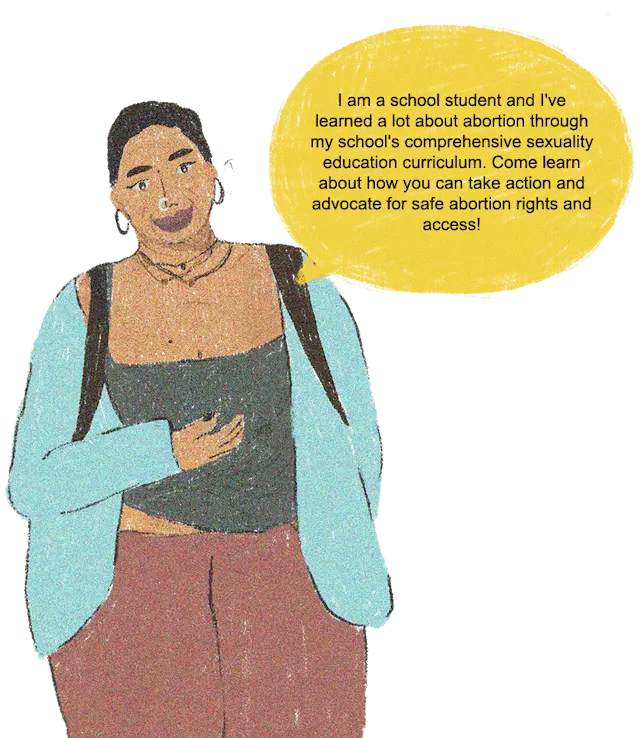

Hover over the characters to gain perspective!

Hover over the characters to gain perspective!

© 2021 SAFE. All rights reserved | Privacy Policy | Credits